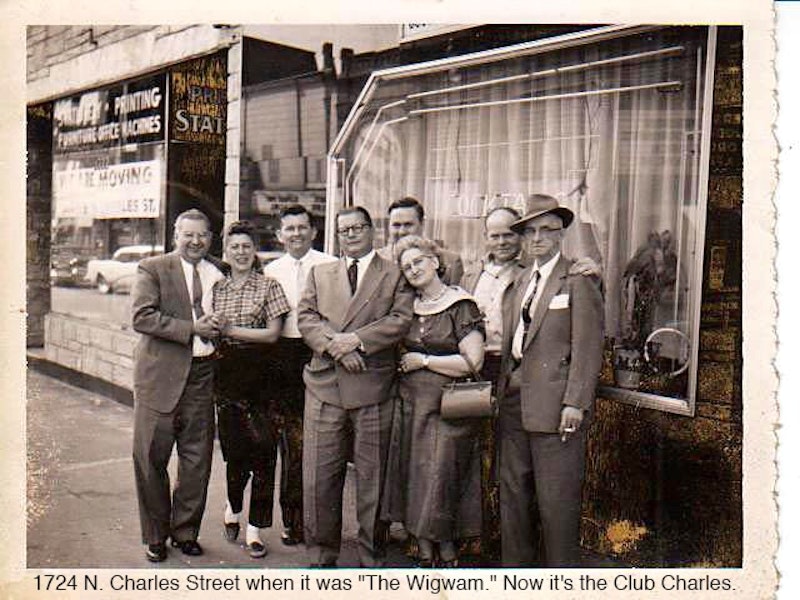

There was once a bar and grill in Baltimore known for its sign advertising “Grub and Firewater.” That was the Wigwam on N. Charles St. and it was my family’s place. Three siblings from Oklahoma via NYC bought what was then the Charles Seafood Restaurant in 1951: my mother Esther West, her brother Bill West, and sister Mary Lou West.

They’d been working in New York nightclubs after the Second World War ended and at some point moved to Baltimore and bought what would become the Wigwam. My mother claimed Native-American ancestry and the bar became known as “that place with the crazy Indians” before it was formalized as the Wigwam. The siblings had lost their naval aviator brother Dick, my namesake, shortly before the war ended and the bar became a favorite hangout of sailors, merchant marines, and veterans of all sorts. The bar eventually was solely owned by Esther and she tried to assist as many of these veterans as she could, providing help that the Veterans Administration simply wasn’t tasked to provide. She found them housing, furnishings and work.

It wasn’t entirely altruistic. As the neighborhood worsened in the early-1970s, she took advantage of their often troubled returns to civilian life by letting the drinkers run up a tab. Many veterans have problems with alcohol. She’d deduct the tab from their assistance checks (which they’d arranged to be mailed in care of her at the bar.) The bar sold alcohol, tobacco, and food. Good food came out of that kitchen, but a lack of decent help led to the kitchen being kept open mostly to keep the liquor license. Esther started selling groceries and clothing from behind the bar. She was like the mayor of Bumville, keeping her supplicants fed, clothed, and blind-drunk.

On the day checks arrived, she’d go over the accounts of the “smokehounds” and make sure their rent was paid (especially if it was one of her apartments they were renting). She’d settle any outstanding tab and give over some of the remaining funds, holding back enough to cover their new tab. These drunks would then wander up the street with a handful of cash and buy booze at a competitor and burn up whatever remaining funds they had. When they reached zero balance it was back to Esther, who always forgave them and extended credit after a good cussing for going up the street.

There used to be a drawer behind the bar near the register that held everyone’s tabs. Full of dated cardstock receipts that the old NCR cash register spit out. On these little cards would be the person’s name and the amount. I’d wager that 75 percent of the paper in that drawer concerned people who were dead or not coming back for some other reason.

Esther’s greatest charity to these men (almost exclusively men) was to arrange healthcare for them when their bodies finally started to fail. To be fair, most of their systems gave out because of service related physical and mental injuries, not necessarily the drinking.

I remember Russian George, but not his last name. He had a thick Russian accent, and was a US veteran who had fought in WW2 for the US. He had a dent in his head big enough enough to hold a pair of AA batteries. When he drank, he’d start crying and pointing to that dent, “I fought for U.S! I almost died for U.S!” And on those days when the government checks arrived (his for the military disability,) he’d sigh after settling up and say, “You owe a penny, you pay a penny.” Every damned time.

There was a drunk we called Indian Willie. I don’t think he was a Native-American, but a lot of people claimed that ancestry to get an in with Esther. He broke both his legs when a dumpster he was inspecting flipped over on him. His system was so deteriorated by that point that he couldn’t heal. Only person I know that died of broken legs. We visited him at Maryland General Hospital downtown and Esther brought along a bottle and some smokes. He was dying, knew it, and that was all he wanted. She obliged.

Another of the Wigwam’s regulars was Bob Appenfelder, loud, dirty, and toothless. Bob was one of those people whose mental illness caused his family to distance themselves by sending him to downtown Baltimore to live. They’d mail enough money each month to pay his rent and booze bills. When Bob was drinking (always!) he liked to remind people that he owned Anheuser-Busch stock. I don’t know if he really did, but he believed he owned that asset and in astronomical amounts. He had anywhere from a million shares to a million billion shares. He was a silly drunk, spouting nonsense on a variety of issues just to get a rise out of the straights. He’d shout a string of curse words as if he had Tourette’s Syndrome, in hopes of generating a reaction from somebody. This was Esther’s bar and foul language only generated reactions from newcomers. But Bob couldn’t stop when he was ahead, so the time came for him to be 86’d from the bar. He’d start totaling up all his Budweiser shares as a delaying tactic, but he was 86’d at least every few weeks because of his general meanness. I noticed the number of shares he claimed rose proportionally with his blood alcohol content.

There were two other “alkies” that frequented the place, Hillbilly and McCloud. Hillbilly was from North Carolina, a house-painting hillbilly whose unemployment checks were addressed to Mr. Charles Sexton in care of the Wigwam. He had someone else’s social security number so he’d get two unemployment checks which he managed to fully drink up single-handedly. He often prostrated himself to Esther in hopes of a free bottle. If he’d do some chores, he’d get that bottle. Once, Esther was working in the liquor room stocking the shelves with a recent delivery and he went to her begging. She told him he could have anything he wanted as long as he wanted nothing. He thought that was high comedy and repeated the tale over the next few days. “Miss Esther said I can have anything I want so long as I don’t want NOTHING!”

His pal McCloud was actually a McLeod, but the popularity of Dennis Weaver’s cowboy cop show at the time made McLeod McCloud. He was a painter when sober (rarely) and also knew how to collect multiple unemployment checks between gigs. McCloud and Hillbilly came as a pair. They drank together, they stumbled up and down Charles St. together, and they roomed together when flophouses were still common. They were the best of friends until one day they got far too blotto and on that day Hillbilly killed McCloud in a drunken fistfight under the Jones Falls Expressway.

A lot of the men who I knew as drunks from the bar were tradesmen. Painters, masons, electricians. Painters were the worst drunks, but don’t fuck with a drunk mason. They’d work until their bills were paid plus one week, then go on a month-long bender with that last week’s pay. If they were still alive, they’d go back to work and repeat the cycle.

One gentleman who frequented the place shared my last name. He was black, I’m white, but after two drinks he always said we were brothers. He wasn’t a tradesman. He worked for Baltimore City Public Schools and when he’d first arrive, he was the kindest and most polite customer I’d get all day. He always wore a suit and tie. In the winter months he added a hat and long camelhair overcoat. Most nights he’d have two drinks and head out early because he had a job and cared about it. But there were nights when someone would buy him a third drink or a fourth and then it was a crapshoot which type of drunk he’d become. Sometimes simply loud and laughing too loud. I loved that guy. But he was a big man and would sometimes push too hard to join another group of drinkers. I remember driving up Charles and seeing him heading south one evening around 11 p.m. The tie was gone. He was stumbling and bleeding from the mouth. That guy I didn’t like so much.

My father spoke of another customer who had throat cancer. He could take nothing by mouth. The lifetime of straight alcohol had taken its toll. Like Indian Willie before him, he knew he was on his deathbed, but he was an alcoholic and simply wanted some booze before going. Maryland General wasn’t cooperating with his dying wish. Persons unknown took him a handful of miniatures and he gratefully poured them directly into his feeding tube.

Esther assumed all her customers of that age were either veterans or widows of veterans. That wasn’t always the case. Over time there were simply old sick drunks, but Esther became the only caregiver for these particular old sick drunks. When there was a death among them, Esther would attempt to contact any known family, but it was very sad how few had next-of-kin. In many cases, it fell to Esther to go through the deceased’s paperwork to find proof of service so that a deserving veteran got a proper funeral.

In several cases, Esther would end up the sole heir to their belongings. Growing up, we cleaned out a few apartments after a customer’s death. They usually had a single-floor rowhouse apartment or a single room in a flophouse hotel. Esther would decide who among her remaining wards needed this sofa or that radio and would make her dispensations accordingly. China and radios were stored for the next needy drunk who showed up claiming Native-American heritage and military service. Paperwork was held onto in case it might be needed for some future purpose. Eventually the important papers and photos were stored in a thrift store briefcase and that would be it. Mostly Esther was looking for proof of military service because one constant veteran’s benefit is a free burial.

In 1981, the Wigwam underwent a remodel and rebranding, re-opening as the Club Charles. Most of the old customers had died and those still around didn’t like the new tunes on the jukebox and found other homes. They’d still come in for a few years to collect their checks, have a drink, and pay homage to Esther.

One customer who died sometime in the 1960s extracted a promise from Esther to look after his son, Russell. Russell and his father were both big men, boxers. Russell had been jumped by a couple of muggers and turned around and beat them to death. The state didn’t look kindly on that and gave him a frontal lobotomy. It changed him, but it wasn’t an improvement. Russell mopped the floors and carried the beer for the Wigwam and even the Club Charles for a few years.

Russell was always teetering on dangerous when he was drinking. He liked to crush one’s hand in a handshake. I didn’t know him before the lobotomy so I can’t speak to the cause of his peculiarities. He believed that a body had “power” as he called it. Drinking and smoking hurt one’s power but only once the empty container reached the landfill (or otherwise destroyed). I can’t recall the precise details but it resulted in Russell collecting every single container he ever used that took his power. His apartment overflowed with garbage bags full of empty liquor bottles, aluminum cans, and cigarette packs.

When I gave Russell change for the pinball machine, I had to assure him that there were no “whores’ quarters” in there. As he explained, “If you get a quarter on Baltimore St., it’s probably a whore’s quarter; it’ll burn up the wires in that pinball machine.” Let that be a warning to everyone. Russell developed a huge stomach tumor and I’m grateful I didn’t have to clean that apartment after he passed away, but according to those who did, he’d “exploded.”

A year or so before Russell died, we’d cleaned out all the aluminum cans from his apartment to help fund a renovation at the Club Charles. It was a lot of bags of cans and they paid for his cremation. Russell had no other family than Esther and his cremated remains stayed in the office at the Club Charles for many years afterwards, accompanied by a briefcase of his personal papers. He was probably the last of Esther’s wards to get that treatment.